The language of the brain

A fundamental issue that limits our understanding of the brain is that of the neural code. We know that neurones provide the basic processing elements underlying brain function. Furthermore, we are beginning to map out the "types" of neurones in different brain areas. However, the ways in which the neurones convey information and pass that information to other neurones (how they talk to each other) remains relatively unclear.

Activity in the nervous system comes in two forms: the "spiking" and the "non-spiking" neurones. In the mammalian nervous system, non-spiking neurones are found in the periphery. For example, neurones in the retina are mostly non-spiking (the signals are encoded in an analogue fashion by the membrane potential). Neurones in the central nervous system are "spiking" neurones. That is, the activity is related to the production on action potentials (signals are encoded by all-or-none unitary events).

It is clear that in certain systems the precise time

of spikes has an important role in the signalling of stimulus related

information. Examples of this include the encoding of auditory pitch in

the auditory nerve and the encoding of the signals from the cold receptors

in the skin. The role of precisely timed spikes in cortical processing

is still under debate. Work in St. Andrews has concentrated on examining

the potential role of precisely timed spikes in visual processing.

The temporal resolution of neural codes: What measures of neural activity matter?

One aspect of our research into neural coding involves consideration of the temporal resolution of neural codes. Research on neural codes in St. Andrews is concerned with the activity of spiking neurones of the visual system. Studies have focussed on (1) which neural codes convey stimulus related information, (2) what are the relationships between different neural codes and (3) can we find evidence that these neural codes might influence behaviour.

If a neural code is of interest, then it should be possible to measure of that code and use it to try and guess which stimulus elicited the response. That is to say, the neural code carries some stimulus related information. For example, let us say that when stimulus B is presented, its presence tends to elicit lots of spikes from the neurone we are studying. On the other hand presentation of stimulus A, C or D tends to elicit only a small number of spikes. If we now try and decode the neural signal, we would guess that if we had counted lots of spikes, stimulus B had been presented. If we counted only a small number of spikes we would guess that the stimulus was either A, C or D. As we can use the response of the neurone to help us guess which stimulus had been presented, we can say that the neurone's activity conveys stimulus related information.

There is little doubt that the "firing rate" of neurones (the number of spikes per second) conveys stimulus related information. In the past decade or so there has been increasing interest in other neural codes. One way of thinking about other neural codes is in the realm of "temporal resolution". The total number of spikes within a long time window (e.g. 500ms) represents the coarse temporal code. Other neural codes then have to "operate" within a finer time scale. For example, the variation in firing rate over time measured with a tmeporal resolution of 10's of milliseconds. Finally, there could be fine temporal codes, where the precise times of individual spikes (millisecond temporal accuracy) convey stimulus related information.

From Oram et al. Philos Trans R Soc 357:987-1001, 2002.

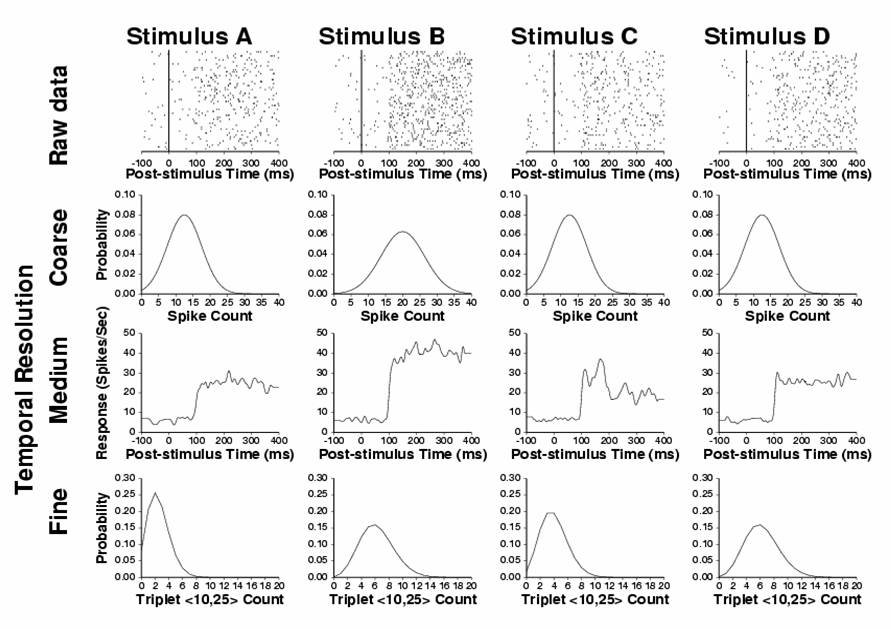

This schematic figure shows possible neural codes which could operate

at different temporal resolutions. Possible responses to four stimuli

(A-D) are shown across the top row in rastergram form (each row of dots

is the response from a single trial, each dot represents the time when

a spike occurred). The second row shows probability or relative frequency

of each spike count (measured over the period 0 – 400 ms post-stimulus

onset) being elicited by each stimulus (variance of spike count is twice

the mean). The spike count distributions are identical for stimuli A,C

and D (mean=12 spikes, variance=24 spikes²), but the spike count

distribution elicited by presentations of stimulus B is different (mean

= 21 spikes, variance=42 spikes²). Thus spike count discriminates

between input stimulus B from the other stimuli (i.e. carries stimulus

related information). The third row plots the spike density function

(firing rate as a function of time) for each of the stimuli (temporal

resolution 5ms). The shape of the spike density function of the responses

to stimulus C is different from those of the responses to stimuli A,

B and D (after adjusting for the changing spike count in the case of

stimulus B). Therefore, the intermediate temporal resolution code can

carry information unavailable from spike count. The bottom row plots

the fine temporal measure of the probability or relative frequency of

observing different numbers of triplet <10,25> in the response

to each presentation of stimuli A-D. Triplet <10,25> is a triplet

of spikes with intervals of 10 and 25 milliseconds. The differences

in the distributions of triplet <10,25> in the responses to stimuli

A, B and C can be attributed to changes in spike count distributions

(A versus B, B versus D) or spike density function (A versus C, C versus

D). The distributions of triplet <10,25> differ for the responses

to stimuli A and D and this difference is not a reflection of differences

in either spike count or spike density function. Therefore, the fine

(1-20 ms) temporal resolution code can carry information unavailable

from either the coarse or intermediate resolution code (spike count

and spike density function shape respectively). Substantial evidence

suggests that the mid-range temporal measures of neural responses carry

information that is unavailable for coarse temporal measures. Recently

it has been speculated that the fine temporal measures of responses

(lower right) may carry yet more information

|

|