What to read | What to think about | What to write

First of all, revise and improve your understanding of Descartes' Dream Argument. And then:

Watch The Matrix. Or at the very least, click here to see a clip. Read Dan Dennett's little essay 'Where am I?'. You can find it in Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology by Daniel C. Dennett. Copyright (I) 1978 by Bradford Books. Or in Hofstadter, D.R. and Dennett, D.C. (1981): The Mind's I: Reflections on Self and Soul, New York: Bantam Books. This latter book contains also other interesting material, together with various comments and reflections on brains-in-vats, and further thoughts which you might find helpful. You can read the original article here.

And then try one of: the next two pieces:

Reason, Truth and History, by Hilary Putnam, CUP 1981, chapter 1, pp.1-21.

Try to work out what Putnam's anti-sceptical manoeuvre is, and how it is supposed to work. What other theses does it commit you to? Do you agree with them? What do you think of Putnam's argument agaist scepticism?

Philosophical Explanations, by Robert Nozick, Clarendon 1981, chapter 3, pp.167-178 & 197-211

This, if you attempt it, is difficult and technical stuff. You will have to work very hard to master it. Again, try to work out Nozick's anti-sceptical manoeuvre actually is. What other theses does his view comit you to? Does his argument work against scepticism?

Both are reprinted in:

And finally, if you have any time left, read

Skepticism: a Contemporary Reader, by K. DeRose & T. Warfield (eds.), OUP 1999.

Which also contains many other recent articles.

The View from Nowhere, by Thomas Nagel, OUP 1986, chapter 5.

And if not, mark it down for later. This is an excellent book, with applications right across philosophy, not just in the small corner you are looking at this week.

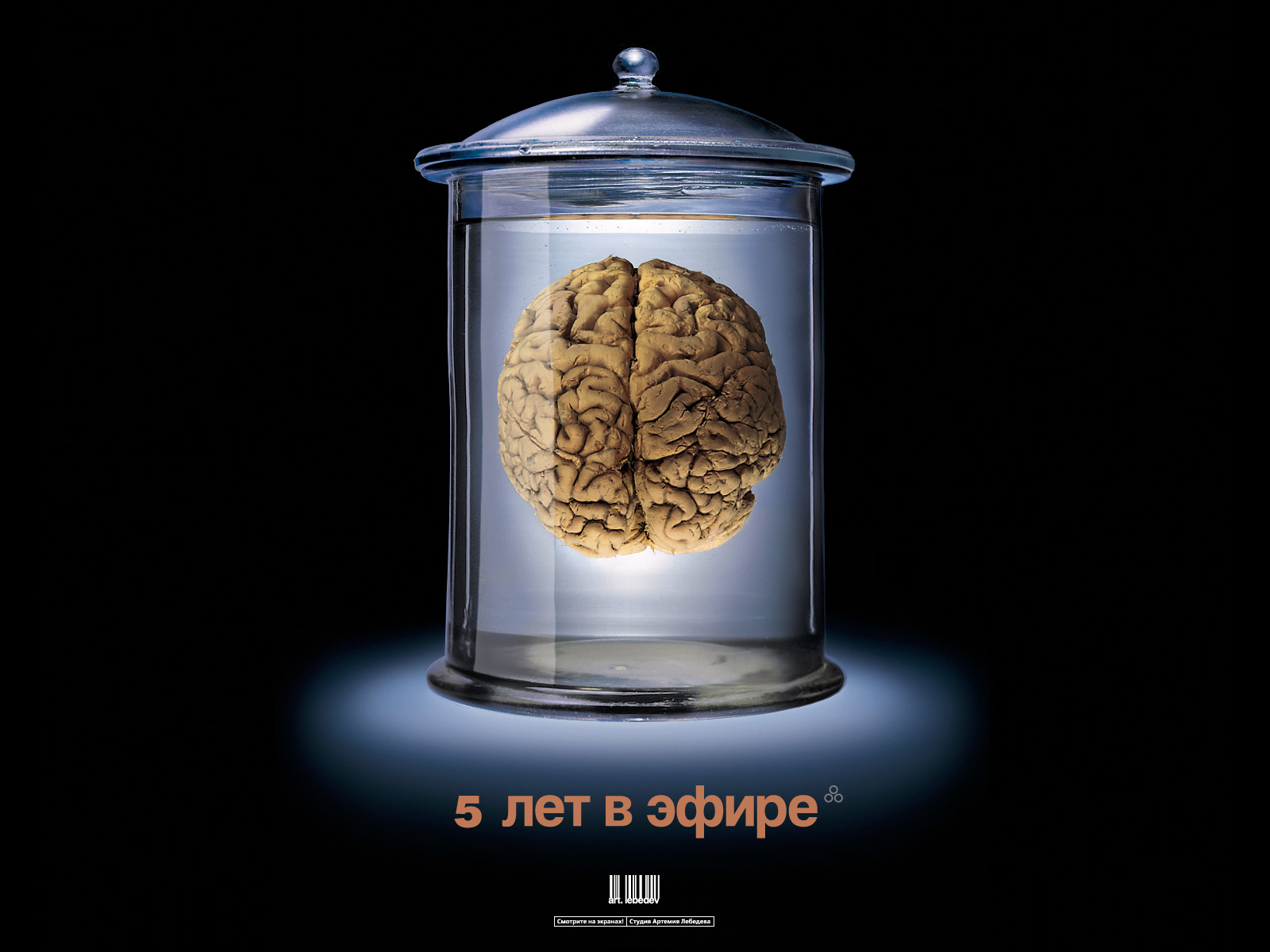

We all believe, do we not, that we are not brains in vats, that we are what we seem to be, flesh and blood creatures of a certain species, where we seem to be - in the solid world of our quotidian experience. In short, we all believe in The Hypothesis of the External World. In its most austere form it goes like this:

My experiences represent and are caused by a world of material objects, which persist through space and time independently of my consciousness.

Indeed, to call this a mere belief seems to already misunderstand its nature. Just try, for a minute, to really imagine that it is false. (Without going totally insane, that is). For us, this is absolute bedrock. We are utterly confident in its truth

The sceptic says that this blithe confidence is utterly unfounded. That we have no reasons whatsoever to back up this 'belief'. So: what are you going to do about it?

Possible lines of thought: Is the Brain-in-a-vat hypothsis coherent? Or is there perhaps some way in which that's only a first impression, so that under closer examination we find that we can't really make sense of it? Or failing that, does the sceptical argument have a fallacious step in it somewhere? Or perhaps we could even agree that the sceptic is right, and nonetheless find a way to live with his conclusion.

This time, take it that your audience is philosophically informed, and has at least come across the broad lines of argument. Outline your own take on the problem, and defend your own account of its proper resolution.Choose your own title. If you would prefer me to impose one, here is a standard Oxford examination question:

Is the hypothesis that you are a brain-in-a-vat coherent? If so, does it follow that you cannot know that you are in Oxford?

And now a farewell from Stanley: