MICROCHIP LASERS - a brief overview, October 1999

Bruce Sinclair, University of St

Andrews

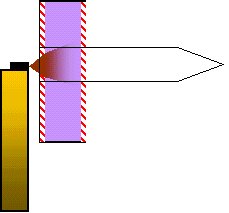

Microchip lasers

are perhaps the ultimate in miniaturisation of diode-pumped solid-state lasers. A thin

etalon of gain material (shown left in purple) has dielectric coatings applied to its

plane surfaces, and a diode laser (shown black with red beam) provides a strongly

localised pump source. The pump also produces thermal and gain related effects that

provide cavity stability mechanisms, allowing the production of a high quality TEM00 beam.

As first demonstrated a decade ago in Nd containing gain materials by Dixon and by

Zayhowski and Mooradian, the short length of these devices allows the generation of

single-frequency radiation in a readily mass produced laser. Scientists at Milan extended this concept into

telecoms applications by using Er-Yb:glass as

the gain material to generate tens of milliwatts of high-purity radiation at 1.5 mm.

Microchip lasers

are perhaps the ultimate in miniaturisation of diode-pumped solid-state lasers. A thin

etalon of gain material (shown left in purple) has dielectric coatings applied to its

plane surfaces, and a diode laser (shown black with red beam) provides a strongly

localised pump source. The pump also produces thermal and gain related effects that

provide cavity stability mechanisms, allowing the production of a high quality TEM00 beam.

As first demonstrated a decade ago in Nd containing gain materials by Dixon and by

Zayhowski and Mooradian, the short length of these devices allows the generation of

single-frequency radiation in a readily mass produced laser. Scientists at Milan extended this concept into

telecoms applications by using Er-Yb:glass as

the gain material to generate tens of milliwatts of high-purity radiation at 1.5 mm.

The functionality of the microchip laser concept can be increased, while still

maintaining its inherent simplicity and robustness, through the use of a

"sandwich" of the gain etalon with another material. This additional material

can take the form of a frequency-doubling crystal to shift the output of Nd devices into

the visible, an electro-optic material to allow for frequency tuning, or a saturable

absorber to permit passive Q-switching.

Work at St Andrews and at Hamburg

has explored intracavity frequency-doubled Nd lasers and produced tens to hundreds of

milliwatts of cw red, green, and blue light. The short cavities had low loss and a small

beam waists. This allowed the generation of significant circulating IR fields, and thus

efficient second harmonic generation. The short cavity lengths also contributed to reduced

intermodal coupling, and hence could remove the intensity instability known as "green

noise". This type of technology was marketed by Uniphase,

amongst others, as a replacement for air-cooled argon ion lasers in the reprographics and

biomedical industries, for example.

Work at St Andrews and at Hamburg

has explored intracavity frequency-doubled Nd lasers and produced tens to hundreds of

milliwatts of cw red, green, and blue light. The short cavities had low loss and a small

beam waists. This allowed the generation of significant circulating IR fields, and thus

efficient second harmonic generation. The short cavity lengths also contributed to reduced

intermodal coupling, and hence could remove the intensity instability known as "green

noise". This type of technology was marketed by Uniphase,

amongst others, as a replacement for air-cooled argon ion lasers in the reprographics and

biomedical industries, for example.

Zayhowski at Lincoln Labs led the way in the

development of passively Q-switched lasers. He sandwiches a slices of Nd:YAG with a slice

of the saturable absorber Cr:YAG to produce cavities about 1mm long. When pumped with one

watt from a fibre-coupled diode these devices produce pulses as short as 218 ps, pulse

energies as high as 14 mJ, time-averaged powers of up to 120

mW, with pulse repetition rates between 8 and 15 kHz. He has also demonstrated

quarter-millijoule output devices pumped with 10 W fibre-coupled diode laser arrays. The

high peak powers and near-ideal spectral and spatial output of all these devices makes

single-pass frequency conversion of their output rather efficient. One-watt pumped

microchip lasers have produced 7 mJ of green and 1.5 mJ of 266 nm at pulse repetition rates around 10 kHz. These short

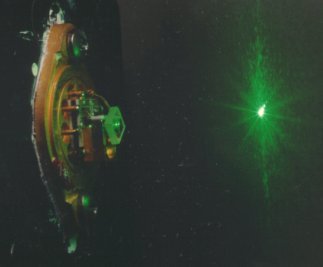

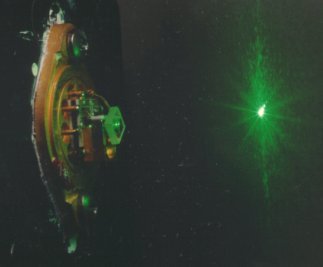

pulses allow for compact LIDAR systems with 1 mm depth resolution, and the high

intensities are useful for laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy. They have also been used

to drive efficient optical parametric oscillators and amplifiers.

In Europe LETI-CEA

with Nanolase have successfully developed passively

Q-switched Nd:YAG lasers using a saturable absorber epitaxially grown on to the Nd:YAG

gain material, though in some systems Nanolase utilise a conventional slice of Cr:YAG.

These high-specification and relatively low-cost lasers are marketed for applications in

micro-fluorescence, ranging, and spectroscopy, amongst others. Devices operating at 1.55 mm and 1.06 mm have potential for use in

collision avoidance systems in cars. Again the ability to generate harmonic wavelengths

efficiently is important for many applications. Keller's group in Zurich has taken passive

Q-switching to a new record, producing 37 ps pulses at 1.06 mm

using a semiconductor saturable absorber, and have also used their SESAM technology at

telecom wavelengths.

There remains much interest in the physics of microchip lasers, both in terms of how

they work, and in their use for experiments in quantum optics.

Microchip lasers have found their own distinctive role. Their robust and readily

mass-produced structures are very attractive. Couple this with their single-frequency cw

performance, or their excellence at generating sub-nanosecond pulses, and one sees that

they are well suited for many applications.

Return to University of St Andrews Microchip Laser Group's Home Page

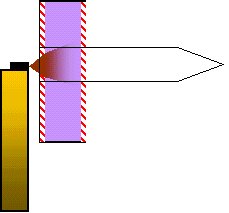

Microchip lasers

are perhaps the ultimate in miniaturisation of diode-pumped solid-state lasers. A thin

etalon of gain material (shown left in purple) has dielectric coatings applied to its

plane surfaces, and a diode laser (shown black with red beam) provides a strongly

localised pump source. The pump also produces thermal and gain related effects that

provide cavity stability mechanisms, allowing the production of a high quality TEM00 beam.

As first demonstrated a decade ago in Nd containing gain materials by Dixon and by

Zayhowski and Mooradian, the short length of these devices allows the generation of

single-frequency radiation in a readily mass produced laser. Scientists at Milan extended this concept into

telecoms applications by using Er-Yb:glass as

the gain material to generate tens of milliwatts of high-purity radiation at 1.5 mm.

Microchip lasers

are perhaps the ultimate in miniaturisation of diode-pumped solid-state lasers. A thin

etalon of gain material (shown left in purple) has dielectric coatings applied to its

plane surfaces, and a diode laser (shown black with red beam) provides a strongly

localised pump source. The pump also produces thermal and gain related effects that

provide cavity stability mechanisms, allowing the production of a high quality TEM00 beam.

As first demonstrated a decade ago in Nd containing gain materials by Dixon and by

Zayhowski and Mooradian, the short length of these devices allows the generation of

single-frequency radiation in a readily mass produced laser. Scientists at Milan extended this concept into

telecoms applications by using Er-Yb:glass as

the gain material to generate tens of milliwatts of high-purity radiation at 1.5 mm. Work at

Work at